On 10 January 2017 FIFA voted to expand the 2026 FIFA World Cup to 48 teams. The surrounding press coverage has considered the implications of expansion from a number of perspectives – fan, financial, and football among others. At Futures, we’ve sought to evaluate the net impact of tournament expansion through a media lens, by modelling global TV audiences based on 19 years of international TV data across more than 60 international markets, whilst making assumptions for 2026. By breaking out the various elements of the new format and using historic data as a baseline, we hope to shed some light on the relative weight of each new element of the 2026 tournament in terms of its impact on viewership. To what extent does more teams and more matches mean more viewers?

Here’s what we’ve incorporated into our model, based on early indications from FIFA and industry commentary:

- A host nation from the Americas

- 16 additional teams and their likely identities

- 16 additional matches

- A three-team group stage with two matches per team and a round of 32 knockout stage

- A win / lose group stage format with penalties replacing draws

- Four matches per day during the group stages with no simultaneous kick-offs

Our prediction

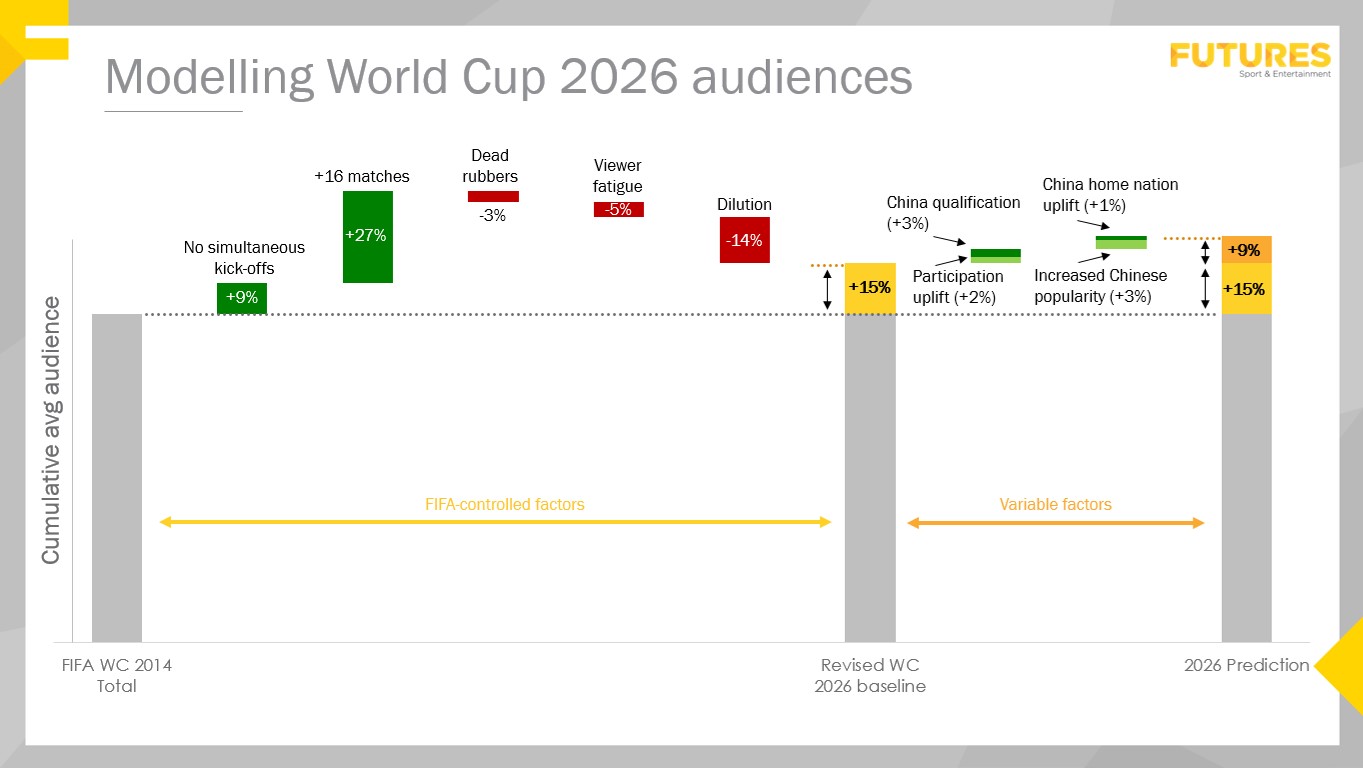

Global audiences will rise by 24% for the 2026 FIFA World Cup, compared with the 2014 tournament. Whilst most elements will lead to an increase in viewership, a couple will lead to decline. These are split out by ‘controlled’ and ‘variable’ elements and spelt out in turn below.

FIFA-controlled factors

To obtain a baseline for 2026, we’ve adjusted 2014 audiences to the new format. The early favourite to host the 2026 World Cup is the USA, making Brazil 2014 - another host in the Americas - the most appropriate tournament to act as a viewership baseline when accounting for differing global time zones. Viewership in key Asian markets dropped by up to 40% when comparing 2006 and 2010 tournaments (held in Europe and Africa, with roughly a -4 to -8 hour time difference) to 2014 in Brazil (roughly -7 to -11 hours).

The increase in number of matches will lead to a 27% increase in viewership, the single largest driver. Importantly, these matches will not be simultaneously broadcast. In the 2014 tournament, viewers were forced to choose between one of two simultaneous matches during the third stage of group matches, reducing the average audience by up to 40% per match versus earlier group stage matches. Scheduling the third round of the group stages on a non-simultaneous basis will drive a further 9% of viewership growth in 2026.

However, this alone is not sufficient as a 2026 baseline. Also at play in the early stages of the tournament is a dilution in quality of participant, an additional fourth match window per day up to the round of 16, and an abolition of the draw in group matches. This last proposed change will increase the incidence of dead rubbers.

The expansion of the UEFA European Championships in 2016 provides a benchmark for decreased viewership per match when lower-ranked participants qualify for a major international tournament

First, dilution of quality. We expect to see a 14% decline in cumulative tournament viewership attributable to a perception of diluted quality of teams. The expansion of the UEFA European Championships in 2016 provides a benchmark for decreased viewership per match when lower-ranked participants qualify for a major international tournament. This decrease has been applied to FIFA World Cup 2026 group stage matches only, after which only 32 teams will remain. That said, low-ranked teams can and do progress beyond the group stages, regardless of tournament expansion. In 2002, 40th-ranked South Korea played 22nd-ranked Turkey for third place; 19th-ranked Croatia finished third in 1998. Three group matches is not a big enough sample to ensure the best teams progress; this level of variability is exacerbated by the switch to a two-match, win / lose group format for 2026, which arguably encourages negative tactics with the prospect of a penalty shootout as a means of taking all three points.

Next, dead rubbers (-3%). The change in scheduling means that if the final match of a given group is a dead rubber, there is no alternative match to watch at the same time. Futures ran 100,000 simulations of a 16-group, 3-team, 2-match format to obtain the incidence of a final match in a group being a dead rubber. Using Elo ratings to seed and group each nation and to obtain a probability of the head-to-head outcome of a match – using win / lose outcomes only - and a randomised schedule, we expect 29% of groups (or 4.3 in every 16) to end with a dead rubber match compared to 19% incidence in a win / lose / draw format, and have adjusted viewership projections accordingly.

Four consecutive matches a day up to the round of 16 means audiences will succumb to some viewing fatigue, or to more selective viewership

Finally, FIFA’s intention to remove simultaneous matches without extending the tournament beyond 32 days means the introduction of a fourth match window per day during the group stages and round of 32. This slot is most likely to be early afternoon, a less favourable slot for viewership in the Americas, but well-suited to European and some Asian markets. More importantly, four consecutive matches a day up to the round of 16 means audiences will succumb to some viewing fatigue, or to more selective viewership among fans unable to watch 8 hours of coverage a day. We expect to see a resulting 5% decline in cumulative tournament viewership from this factor in isolation.

These three elements have been applied to the group stage, and, in the case of viewer fatigue, round of 32 projections. Overall, the change in audiences due to the restructuring of the FIFA World Cup will be 15% net growth.

Variable factors

The qualification of China would outweigh the combined uplift of any (realistic) combination of 15 other qualifiers

Building on this baseline, we’ve speculated on the identity of the 16 new teams. The main beneficiaries will be Asian and African nations; both confederations could see nine representatives each in 2026 (compared to four and five teams, respectively, in 2014). Participation in a tournament under these conditions is associated with roughly 20% uplift in viewership in a given market, which potentially includes some populous nations not present at Brazil 2014, such as Egypt (CAF) and Turkey (UEFA). However, by far the most important variable on global viewership is whether China qualifies. The qualification of China would outweigh the combined uplift of any (realistic) combination of 15 other qualifiers. 15 additional markets increases our 2026 aggregated viewership forecast by 2%. China’s qualification alone yields an extra 3%.

Further to this, we’ve extrapolated current trends in Chinese football interest and investment to understand how 2026 viewership might be impacted by greater football popularity in China. Making a modest assumption that the TV popularity of the FIFA World Cup in China grows by two percentage points by 2026, and applying this uplift only to stages in which China is still competing (assuming group stage elimination), aggregate viewership increases by 3%. Futures also expects to see a 1% increase in aggregated viewership from the two matches in which China competes – the home nation uplift – after bringing domestic viewership in line with that of other markets of a similar footballing pedigree.

World Cup final thoughts

More teams and more matches does indeed mean more viewers. Adding 16 matches is the single biggest driver of viewership increase, even after revising down to adjust for the unintended consequences of perceived diluted quality and viewership fatigue. It’s in the various permutations of a restructured tournament, however, where the marginal increases in viewership accumulate. The presence of the China national team, along with related assumptions on popularity and progress, account for over half the variable uplift. We’d possibly see a similar impact were the India national side to qualify, or to a lesser extent, Indonesia. However, both of these scenarios seem unlikely. China last qualified for a major tournament in 2002, and are currently ranked 81st in the world. Yet with a fledgling domestic league, and as the eighth-ranked nation in AFC with an expected quota of nine Asian sides in 2026, China has a very real chance of qualifying in 2026.

The FIFA World Cup holders have been eliminated in the group stages in three of the last four tournaments, so there is precedent for upsets

There are additional variables that have been omitted from this model. Scheduling European teams to play afternoon matches while western hemisphere nations play evening matches essentially creates two local primetime windows a day, a tactic FIFA has previously adopted to some extent. In 2026, we expect two fewer rest days than in previous tournaments, in order to maintain a 32-day tournament length. Scheduling these on weekdays preserves the appeal and feasibility of watching of back-to-back matches on weekends. In addition, our model does not predict where favourites will lose a match. In a win / lose group stage, with no draws, the underdogs’ chances of victory increase. The FIFA World Cup holders have been eliminated in the group stages in three of the last four tournaments, so there is precedent for upsets. Should this happen to the 200m-strong Brazil (in a tournament held in the Americas), the impact on viewership would be far greater than, say, the early elimination of 46m Spain in 2014.

What we do know is that as the world’s most popular sport, expansion only perpetuates global interest. 131 of FIFA’s 208 members have never played in a FIFA World Cup, but expansion provides a carrot to those members. As TV penetration increases in the developing world, the 2026 FIFA World Cup is in line to leave the biggest global TV footprint yet.